|

|

Osho on Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Khan and

Alauddin Khan

Osho - I have heard Ravi Shankar play on the

sitar. He has everything one can imagine: the personality of a singer,

the mastery of his instrument, and the gift of innovation, which is rare

in classical musicians. He is immensely interested in the new. He has

played with Yehudi Menuhin. No other Indian sitar player would be ready

to do it because no such thing has ever happened before. Sitar with a

violin! Are you mad? But innovators are a little mad, that's why they

are capable of innovation.

The so-called sane people live orthodox lives from

breakfast till bed. Between bed and breakfast, nothing should be said.

Not that I am afraid of saying it, I am talking about them. They live

according to the rules. They follow lines. But innovators have to go

outside the rules. Sometimes one should insist on not following the

lines, just for not following's sake, and it pays, believe me. It pays

because it always brings you to a new territory, perhaps of your own

being. The medium may be different but the person inside you, playing

the sitar, or the violin, or the flute, is the same: different routes

leading to the same point, different lines from the circle leading to

the same center. Innovators are bound to be a little crazy,

unconventional... and Ravi Shankar has been unconventional.

First: he is a pandit, a brahmin, and he married a

Mohammedan girl! In India one cannot even dream of it -- a brahmin

marrying a Mohammedan girl! Ravi Shankar did it. But it was not just any

Mohammedan girl, it was the daughter of his master. That was even more

unconventional. That means for years he had been hiding it from his

master. Of course the master immediately allowed the marriage, the

moment he came to know. He not only allowed, he arranged the marriage.

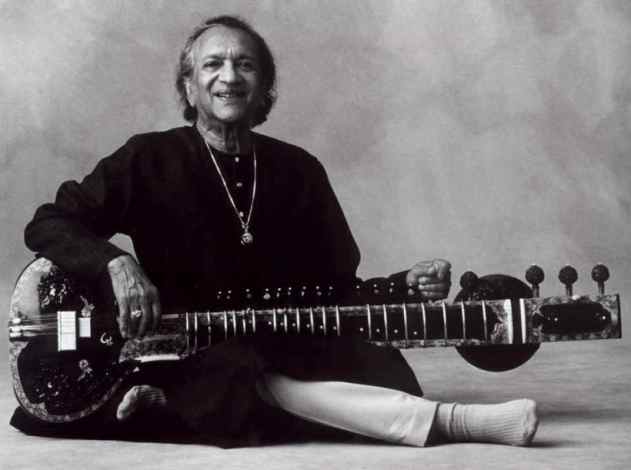

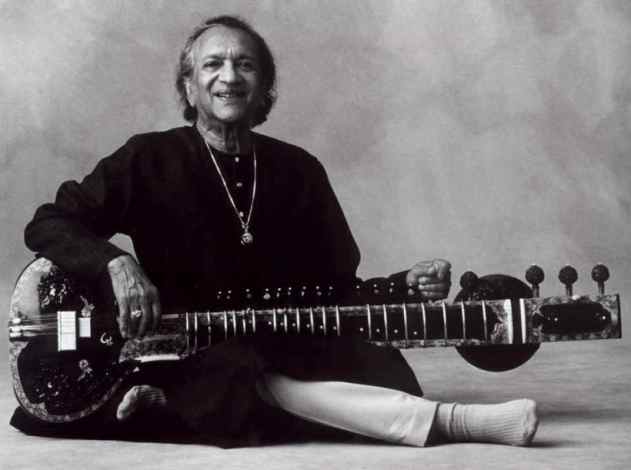

Pandit Ravi Shankar

He too was a revolutionary, of a far greater range

than Ravi Shankar. Alauddin Khan was his name. I had gone to see him

with Masto. Masto used to take me to rare people. Alauddin Khan was

certainly one of the most unique people I have seen. He was very old. He

died only after completing the century.

When I met him he was looking towards the ground.

Masto didn't say anything either. I was a little puzzled. I pinched

Masto, but he remained as if I had not pinched him. I pinched him

harder, but still he remained as if nothing had happened. Then I really

pinched him, and he said, "Ouch!"

Then I saw those eyes of Alauddin Khan -- although he

was so old you could read history in the lines of his face. He had seen

the first revolution in India. That was in 1857, and he remembered it,

so he must have been at least old enough to remember. And he had seen a

whole century pass by, and all that he did this whole time was practice

the sitar. Eight hours, ten hours, twelve hours each day; that's the

classical Indian way. It's a discipline, and unless you practice it you

soon lose the grip over it, it is so subtle. It is there only if you are

in a certain state of preparedness, otherwise it is gone.

A master is reported to have once said, "If I don't

practice for three days, the crowd notices it. If I don't practice for

two days, the experts notice it. If I don't practice for one day, my

disciples notice it. As far as I am concerned, I cannot stop for a

single moment. I have to practice and practice, otherwise I immediately

notice. Even in the morning, after a good sleep, I notice something is

lost."

Indian classical music is a hard discipline, but if

you impose it upon yourself, it gives you immense freedom. Of course, if

you want to swim in the ocean, you have to practice. And if you want to

fly in the sky, then naturally it is apparent that immense discipline is

required, but it cannot be imposed by somebody else. Anything imposed

becomes ugly. That's how the word "discipline" became ugly, because it

has become associated with the father, the mother, the teacher, and all

kinds of people who don't understand a single thing about discipline.

They don't know the taste of it.

The master was saying, "If I don't practice even for a

few hours, nobody notices, but of course I notice the difference." One

has to continuously practice, and the more you practice, the more you

become practiced in practice. It becomes easier. Slowly, slowly, a

moment comes when discipline is no longer a practice, but enjoyment.

I am talking about classical music, not about my

discipline. My discipline is enjoyment from the very beginning, or from

the beginning of enjoyment. I will tell you about it later on....

I have heard Ravi Shankar many times. He has the

touch, the magic touch, which very few people have in the world. It was

by accident that he touched the sitar. Whatsoever he touched would have

become his instrument. It is not the instrument, it is always the man.

He fell in love with Alauddin's vibe, and Alauddin was of a far greater

height -- thousands of Ravi Shankars joined together, stitched together

rather, could not reach to his height. Alauddin was certainly a rebel.

Not only an innovator, but an original source of music. He brought many

things to music.

Today, almost all the great musicians in India are his

disciples. It is not without reason. All kinds of musicians would come

just to touch Baba's feet: sitarists, dancers, flutists, actors, and

whatnot. That's how he was known, just as "Baba," because who would use

his name, Alauddin?

When I saw him, he was already beyond ninety;

naturally, he was a Baba. That simply became his name. And he was

teaching all kinds of instruments to so many kinds of musicians. You

could have brought any instrument and you would have seen him play it as

if he had done nothing else but play that instrument for his whole life.

He lived very close to the university where I was,

just a few hours' journey away. I used to visit him once in a while,

whenever there was no festival. I make this point because there were

always festivals. I must have been the only one to ask him, "Baba, can

you give me the dates when there are no festivals here?"

He looked at me and said, "So, now you have come to

take even those away too." And with a smile he gave me three dates.

There were only three days in the whole year when there was not a

festival. The reason was there were all kinds of musicians with him,

Hindus, Mohammedans, Christians, and every festival happened there, and

he allowed them all. He was, in a real sense, a patriarch, a patron

saint.

I used to visit him on those three days, when he was

alone, and there was no crowd around. I told him, "I don't want to

disturb you. You can sit silently. If you want to play your veena it is

up to you, or whatsoever. If you want to recite the KORAN, I would love

it. I have come here just to be part of your milieu."

He wept like a child. It took me a little time to wipe

his tears away and ask, "Have I hurt you?"

He said, "No, not at all. It just touched my heart so deeply that I

could not find anything else to do but cry. And I know that I should not

cry. I am so old and it is inappropriate, but has one to be appropriate

all the time?"

I said, "No, at least not when I'm here." He started laughing, and the

tears in his eyes, and the laughter on his face, both together, were

such a joy.

Masto had brought me to him. Why? I will just say a few more things

before I can answer it....

I have heard Vilayat Khan, another great sitarist,

perhaps a little greater than Ravi Shankar, but he is not an innovator.

He is utterly classical, but listening to him even I loved classical

music. Ordinarily I don't love anything classical, but he plays so

perfectly you cannot help yourself. You have to love it, it is not in

your hands. Once a sitar is in his hands, you are not in your own hands.

Vilayat Khan is pure classical music. He will not allow any pollution.

He will not allow anything popular. I mean "pop," because in the West

unless you say pop nobody will understand what is popular. It is just

the old "popular" cut short -- badly cut, bleeding.

I have heard Vilayat Khan, and I would like to tell

you a story about one of my very rich disciples -- that is circa 1970,

because since then I have not heard anything of them. They are still

there. I have inquired about their well-being, but sannyas has made so

many people afraid, particularly the rich ones.

This family was one of the richest in India. I was amazed when the wife

told me, "You are the only man to whom I can say it: for ten years I

have been in love with Vilayat Khan."

I said, "What is wrong with that? Vilayat Khan? -- nothing is wrong."

She said, "You don't understand. I don't mean his sitar, I mean him."

I said, "Of course -- what would you do with his sitar without him?"

She hit her head with her hand and said, "Can't you understand anything

at all?"

I said, "Looking at you, it seems not. But I do understand that you love

Vilayat Khan. It is perfectly good. I am just saying that there is

nothing wrong it it."

At first she looked at me in disbelief, because in

India, if you say such a thing to a religious man -- a Hindu wife

falling in love with a Mohammedan musician, singer or dancer -- you

cannot have his blessing, that much is certain. He may not curse you,

but most likely he will; even if he can forgive you, even that is too

modern, ultra-modern.

"And," I said to her, "there is nothing wrong in it. Love, love

whomsoever you want to love. And love knows no barriers of caste or

creed."

She looked at me as if I were the one who had fallen

in love, and she was the saint I was talking to. I said, "You are

looking at me as if I have fallen in love with him. That too is true. I

also love the way he plays, but not the man." The man is arrogant, which

is very common in artists.

Ravi Shankar is even more arrogant, perhaps because he

is a brahmin too. That is like having two diseases together: classical

music, and being a brahmin. And he has a third dimension to his disease

too, because he married the great Alauddin's daughter; he is his

son-in-law.

Alauddin was so respected that just to be his

son-in-law was enough proof that you are great, a genius. But

unfortunately for them, I had also heard Masto. And the moment I heard

him I said, "If the world knew about you they would forget and also

forgive all these Ravi Shankars and Vilayat Khans."

Source - Osho Book Glimpses of a Golden Childhood"

Related Osho

Discourses:

Osho on Sitarist Hazrat Vilayat

Ali Khan

Osho on Ravi Shankar Guru

Alauddin Khan Enlightenment

First Meditation and then out of Meditation comes

Creativity

Osho - Is it ever possible to paint a totally satisfying

Painting?

Anything

can be creative - you bring that quality to the activity

Osho

on Art and Enlightenment, The world needs enlightened

Art

Osho on famous people:

Alan Watts,

Alauddin Khan,

Albert

Einstein,

Adolf

Hitler,

Confucius,

Edmund Burke,

Friedrich Nietzsche,

George Santayana,

Karl Marx,

Ludwig Wittgenstein,

Machiavelli,

Madame Blavatsky,

Mahatma

Gandhi,

Marilyn Monroe,

Martin

Buber,

Mother Teresa,

Nijinsky,

Sanjay Gandhi,

Shakuntala Devi,

Somerset Maugham,

Soren Kierkegaard,

Subhash Chandra Bose,

Trotsky,

Vincent van Gogh,

Vinoba Bhave, Werner Erhard

^Top

Back to Osho Discourses |

|