|

|

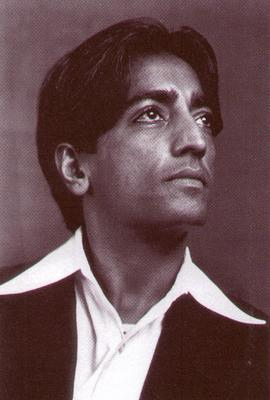

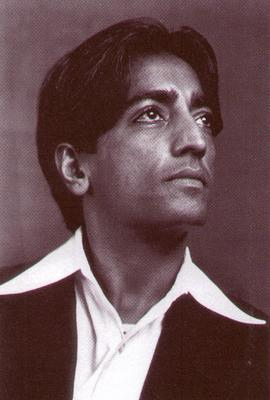

Jiddu Krishnamurti - Understanding

exists in the interval between two thoughts

Question: You say that reality or understanding exists

in the interval between two thoughts. Will you please explain.

Jiddu

Krishnamurti : This is really a different way of asking the

question, "What is meditation?" As I answer this question, please

experiment with it, discover how your own mind works, which is after all

a process of meditation. I am thinking aloud with you, not superficially

- I have not studied. I am just thinking aloud with you about the

question, so that we can all journey together and find the truth of this

question.

The questioner asks about the interval between two thoughts, in which

there can be understanding. Before we can inquire into that, we must

find out what we mean by thought. What do you mean by thinking? Is this

getting a little too serious? You must have patience to listen to it.

When you think something - thought being an idea - what do you mean by

that? Is not thought a response to influence, the outcome of social,

environmental influence? Is not thought the summation of all experience

reacting? Say, for example, you have a problem, and you are trying to

think about it, to analyze it, to study it. How do you do that? Are you

not looking at the present problem with the experience of yesterday -

yesterday being the past - with past knowledge, past history, past

experience? So, that is the past, which is memory, responding to the

present; and this response of memory to the present you call thinking.

Thought is merely the response of the past in

conjunction with the present, is it not, and for most of us thought is a

continuous process. Even when we are asleep, there is constant activity

in the form of dreams; there is never a moment when the mind is really

still. We project a picture and live either in the past or the future,

like many old and some young people do, or like the political leaders

who are always promising a marvelous utopia. (Laughter) And we accept it

because we all want the future, so we sacrifice the present for the

future, but we cannot know what is going to happen tomorrow or in fifty

years' time.

So, thought is the response of the past in conjunction with the present;

that is, thought is experience responding to challenge, which is

reaction. There is no thought if there is no reaction. Response is the

past background - you respond as a Buddhist, a Christian, according to

the left or to the right. That is the background, and that is the

constant response to challenge - and that response of the past to the

present is called thinking. There is never a moment when thought is not.

Have you not noticed that your mind is incessantly

occupied with something or other - personal, religious, or political

worries? It is constantly occupied; and what happens to your mind, what

happens to any machinery that is in constant use? It wears away. The

very nature of the mind is to be occupied with something, to be in

constant agitation, and we try to control it, to dominate it, to

suppress it; and if we can succeed, we think we have become great saints

and religious people, and then we stop thinking.

Now, you will see that in the process of thinking there is always an

interval, a gap, between two thoughts. As you are listening to me, what

exactly is happening in your mind? You are listening, perhaps

experiencing what we are talking about, waiting for information, the

experience of the next moment. You are watchful, so there is passive

watching, alert awareness. There is no response; there is a state of

passiveness in which the mind is strongly aware, yet there is no thought

- that is, you are really experiencing what I am talking about. Such

passive watchfulness is the interval between two thoughts.

Suppose you have a new problem - and problems are always new - how do

you approach it? It is a new problem, not an old one. You may recognize

it as old, but as long as it is a problem, it is always new. It is like

one of those modern pictures to which you are entirely unaccustomed.

What happens if you want to understand it? If you approach it with your

classical training, your response to that challenge, which is that

picture, is rejection; so if you want to understand the picture, your

classical training will have to be put aside - just as, if you want to

understand what I am talking about, you have to forget you are a

Buddhist, a Christian, or whatnot.

You must look at the picture free of your classical

training, with passive awareness and watchfulness of mind, and then the

picture begins to unfold itself and tell its story. That is possible

only when the mind is in a state of watchfulness, without trying to

condemn or justify the picture; it comes only when thought is not, when

the mind is still. You can experiment with that and see how

extraordinarily true is a still mind. Only then is it possible to

understand. But the constant activity of the mind prevents the

understanding of the problem.

To put it around the other way, what do you do when you have a problem,

an acute problem? You think about it, don't you? What do you mean by

"think about it"? You mean working for an answer, searching for an

answer, according to your previous conclusions. That is, you try to

shape the problem to fit certain conclusions which you have, and if you

can make it fit, you think you have solved it. But problems are not

solved by being put into the pigeonholes of the mind.

You think about the problem with the memory of past

conclusions and try to find out what Christ, Buddha, X, Y, or Z has

said, and then apply those conclusions to the problem. Thereby you do

not solve the problem but cover it up with the residue of previous

problems. When you have a really big and difficult problem, that process

will not work. You say you have tried everything and you cannot solve

it. That means you are not waiting for the problem to tell its story.

But when the mind is relaxed, no longer making an effort, when it is

quiet for just a few seconds, then the problem reveals itself and it is

solved. That happens when the mind is still, in the interval between two

thoughts, between two responses.

In that state of mind understanding comes, but it

requires extraordinary watchfulness of every movement of thought. When

the mind is aware of its own activity, its own process, then there is

quietness. After all, self-knowledge is the beginning of meditation, and

if you do not know the whole, total process of yourself, you cannot know

the importance of meditation. Merely sitting in front of a picture or

repeating phrases is not meditation. Meditation is a part of

relationship; it is seeing the process of thought in the mirror of

relationship. Meditation is not subjugation but understanding the whole

process of thinking. Then thought comes to an end, and only in that

ending is there the beginning of understanding.

Source: Jiddu Krishnamurti Third Talk in

Colombo 1949/50

^Top

Back to Krishnamurti Meditation |

|