|

|

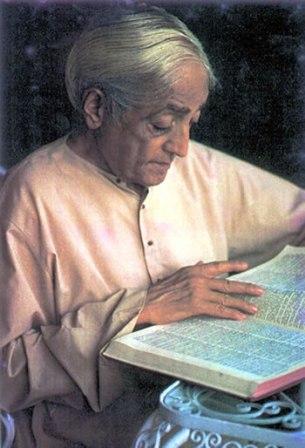

Jiddu Krishnamurti on What is

death

Jiddu Krishnamurti - We have been exploring many

problems which concern our daily life because without understanding

these daily problems of conflict, greed, ambition, envy, the travail of

love, and so on - without understanding them completely - it is utterly

impossible to discover for oneself whether there is something beyond the

things that the brain puts together: the everyday respectable morality,

the inventions of the various churches throughout the world, the

obviously materialistic outlook, and the intellectual attitude towards

life.

Now, it seems to me that any human problem which continues to be a

problem inevitably dulls the mind and makes it insensitive because the

mind merely goes round in circles without ever coming out of its

confusion and misery. So it is vitally necessary to understand each

problem and be finished with it as it arises. I think very few of us

realize that if any human problem is not resolved immediately, it gives

to the mind a sense of continuity in which there is unending conflict,

and this makes the mind insensitive, dull, stupid.

This fact must be

clearly understood, and also it must be understood that we are not

talking in terms of any particular system of philosophy, or looking at

life .along any special line of thought. As you know, we have discussed

many things, but not from either an Oriental or an Occidental point of

view. We have tackled each problem, not as Christians or Hindus or Zen

Buddhists or from any other slanted viewpoint, but simply as rational,

intelligent human beings, without any bias or neuroticism.

This morning I would like to talk about an important question, which is

that of death - death not only of the individual, but death as an idea

which exists throughout the world and which has been carried on as a

problem for centuries without ever being resolved. There is not only the

particular individual's fear of death but also an enormous, collective

attitude towards death - in Asia as well as in the Western countries -

which has to be understood. So we are going to consider together this

whole issue.

In considering such a vast and significant problem, words are only

intended to enable us to communicate, to have communion with each other.

But the word itself can easily become a hindrance when we are trying to

understand this profound question of death, unless we give our complete

attention to it, and not just verbally, flippantly or intellectually try

to find a reason for its existence.

Before, or perhaps in the process of understanding this extraordinary

thing called death, we shall have to understand also the significance of

time, which is another great factor in our lives. Thought creates time,

and time controls and shapes our thought. I am using the word time, not

only in the chronological sense of yesterday, today, and tomorrow, but

also in the psychological sense - the time which thought has invented as

a means to arrive, to achieve, to postpone. Both are factors in our

lives, are they not? One has to be aware of chronological time;

otherwise, you and I couldn't meet here at eleven o'clock. Chronological

time is obviously necessary in the events of our life - that is a

simple, clear matter which need not be gone into very deeply.

So what we have to explore, discuss, and understand is

the whole psychological process which we call time. Please, as I have

been saying at every meeting here, if you merely hear the words and do

not see the implications behind the words, I am afraid we cannot go very

far. Most of us are enslaved by words and by the concept or formula

which the words have put together. Do not just brush this aside because

each one of us has a formula, a concept, an idea, an ideal - rational,

irrational, or neurotic - according to which he is living. The mind is

guiding itself by some pattern, by a particular series of words which

have been made into a concept, a formula.

This is true of each one of us, and please make no

mistake about it - there is an idea, a pattern according to which we are

shaping our lives. But if we are to understand this question of death

and life, all formulas, patterns, and ideations - which exist because we

do not understand living - must entirely go. A man who is living

totally, completely, without fear, has no idea about living. His action

is thought, and his thought is action; they are not two separate things.

But because we are afraid of the thing called death, we have divided it

from life; we have put life and death in two separate watertight

compartments with a great space between them and live according to the

word, according to the formula of the past, the tradition of what has

been; and a mind that is caught in this process can never possibly see

all the implications of death and of life, nor understand what truth is.

So, when you inquire with me into this whole question, if you inquire as

a Christian, a Buddhist, a Hindu, or what you will, you will be

completely at a loss. And if you bring to this inquiry the residue of

your various experiences, the knowledge which you have acquired from

books, from other people, again you will not only be disappointed but

rather confused. The man who would really inquire must first be free of

all these things which make up his background - and that is our greatest

difficulty.

One must be free from the past, but not as a reaction,

because without this freedom one cannot discover anything new.

Understanding is freedom. But, as I said the other day, very few of us

want to be free. We would rather live in a secure framework of our own

making, or in a framework put together by society. Any disturbance

within that pattern is very disquieting, and rather than be disturbed,

we live a life of negligence, death, and decay.

To inquire into this enormous question of death, we must not only be

choicelessly aware of our slavery to formulas, concepts, but also of our

fears, our desire for continuity, and so on. To inquire, we must come to

the problem afresh. Please, this is really very important. The mind must

be clear and not be caught in a concept or an idea if one would go into

something which is quite extraordinary - as death must be. Death must be

something extraordinary, not this thing that we try to cheat and are

afraid of.

Psychologically we are slaves to time - time being the memory of

yesterday, of the past, with all its accumulated experiences; it is not

only your memory as that of a particular person but also the memory of

the collective, of the race, of man throughout the ages. The past is

made up of man's individual and collective sorrows, miseries, joys, his

extraordinary struggle with life, with death, with truth, with society.

All that is the past, yesterday multiplied by thousands; and for most of

us the present is the movement of the past towards the future. There are

no such exact divisions as the past, the present, and the future. What

has been, modified by the present, is what will be. That is all we know.

The future is the past modified by the accidents of

the present; tomorrow is yesterday reshaped by the experiences,

reactions, and knowledge of today. This is what we call time. Time is a

thing that has been put together by the brain, and the brain in turn is

the result of time, of a thousand yesterdays. Every thought is the

result of time; it is the response of memory, the reaction of

yesterday's longings, frustrations, failures, sorrows, impending

dangers; and with that background, we look at life, we consider

everything. Whether there is God or no God, what the function of the

state is, the nature of relationship, how to overcome or to adjust

oneself to jealousy, anxiety, guilt, despair, sorrow - we look at all

these questions with that background of time.

Now, whatever we look at with that background is distorted, and when the

crisis demanding attention is very great, if we look at it with the eyes

of the past, we either act neurotically, which is what most of us do, or

we build for ourselves a wall of resistance against it. That is the

whole process of our life.

Please, I am verbally exposing these things, but if you merely look at

the words and do not observe your own process of thinking, which is to

see yourself as you are, then when you leave here this morning, you will

not have a complete understanding of death, and there must be that

understanding if you are to be free of fear and enter into something

quite different.

So, we are everlastingly translating the present in terms of the past,

and thereby giving a continuity to what has been. For most of us, the

present is the continuation of the past. We meet the everyday happenings

of our life - which always have their own newness, their own

significance - with the dead weight of the past, thereby creating that

which we call the future. If you have observed your own mind, not only

the conscious, but also the unconscious, you will know that it is the

past, that there is nothing in it which is new, nothing which is not

corrupted by the past, by time. And there is what we call the present.

Is there a present untouched by the past? Is there a present which does

not condition the future?

Probably you have not thought about this before, and we shall have to go

into it a little bit. Most of us just want to live in the present

because the past is so heavy, so burdensome, so inexhaustible, and the

future so uncertain. The modern mind says, ''Live completely in the

present. Don't bother about what will happen tomorrow, but live for

today. Life is such a misery anyhow, and the evil of one day is enough,

so live each day completely and forget everything else.'' That is

obviously a philosophy of despair.

Now, is it possible to live in the present without bringing into it

time, which is the past? Surely, you can live in that totality of the

present only when you understand the whole of the past. To die to time

is to live in the present, and you can die to time only if you have

understood the past, which is to understand your own mind - not only the

conscious mind which goes to the office every day, gathers knowledge and

experience, has superficial reactions, and all the rest of it, but also

the unconscious mind, in which are buried the accumulated traditions of

the family, of the group, of the race.

Buried in the unconscious also is the enormous sorrow

of man and the fear of death. All that is the past, which is yourself,

and you have to understand it. If you do not understand that; if you

have not inquired into the ways of your own mind and heart, into your

greed and sorrow; if you do not know yourself completely, you cannot

live in the present.

To live in the present is to die to the past. In

the process of understanding yourself, you are made free of the past,

which is your conditioning - your conditioning as a communist, a

Catholic, a Protestant, a Hindu, a Buddhist, the conditioning imposed

upon you by society and by your own greeds, envies, anxieties, despairs,

sorrows, and frustrations. It is your conditioning that gives continuity

to the 'me', the self.

As I was pointing out the other day, if you do not know yourself, your

unconscious as well as your conscious states, all your inquiry will be

twisted, given a bias. You will have no foundation for thinking which is

rational, clear, logical, sane. Your thinking will be according to a

certain pattern, formula, or set of ideas - but that is not really

thinking. To think clearly, logically, without becoming neurotic,

without being caught in any form of illusion, you have to know this

whole process of your own consciousness, which is put together by time,

by the past. And is it possible to live without the past? Surely, that

is death. Do you understand? We will come back to the question of the

present when we have seen for ourselves what death is.

What is death? This is a question for the young and for the old, so

please put it to yourself. Is death merely the ending of the physical

organism? Is that what we are afraid of? Is it the body that we want to

continue? Or is it some other form of continuance that we crave? We all

realize that the body, the physical entity, wears out through use,

through various pressures, influences, conflicts, urges, demands,

sorrows. Some would probably like it if the body could be made to

continue for 150 years or more, and perhaps the doctors and scientists

together will ultimately find some way of prolonging the agony in which

most of us live. But sooner or later the body dies, the physical

organism comes to an end. Like any machine, it eventually wears out.

For most of us, death is something much deeper than the ending of the

body, and all religions promise some kind of life beyond death. We crave

a continuity, we want to be assured that something continues when the

body dies. We hope that the psyche, the 'me' - the 'me' which has

experienced, struggled, acquired, learned, suffered, enjoyed; the 'me'

which in the West is called the soul, and by another name in the East -

will continue. So what we are concerned with is continuity, not death.

We do not want to know what death is; we do not want to know the

extraordinary miracle, the beauty, the depth, the vastness of death.

We don't want to inquire into that something which we

don't know. All we want is to continue. We say, ''I who have lived for

forty, sixty, eighty years; I who have a house, a family, children, and

grandchildren; I who have gone to the office day after day for so many

years; I who have had quarrels, sexual appetites - I want to go on

living.'' That is all we are concerned with. We know that there is

death, that the ending of the physical body is inevitable, so we say,

''I must feel assured of the continuity of myself after death.'' So we

have beliefs, dogmas, resurrection, reincarnation - a thousand ways of

escaping from the reality of death; and when we have a war, we put up

crosses for the poor chaps who have been killed off. This sort of thing

has been going on for millennia.

Now, we have never really given our whole being to find out what death

is. We always approach death with the condition that we must be assured

of a continuity hereafter. We say, ''I want the known to continue'' -

the known being our qualities, our capacities, the memory of our

experiences, our struggles, fulfillments, frustrations, ambitions; and

it is also our name and our property. AH that is the known, and we want

it all to continue. Once we are granted the certainty of that

continuance, then perhaps we may inquire into what death is, and whether

there is such a thing as the unknown - which must be something

extraordinary to find out.

So you see the difficulty. What we want is continuance, and we have

never asked ourselves what it is that makes for continuance, that gives

rise to this chain, this movement of continuity. If you observe, you

will see that it is thought alone which gives a sense of continuance -

nothing else. Through thought you identify yourself with your family,

with your house, with your pictures or poems, with your character, with

your frustrations, with your joys. The more you think about a problem,

the more you give root and continuance to that problem.

If you like someone, you think about that person, and

this very thought gives a sense of continuity in time. Obviously, you

have to think, but can you think for the moment, at the moment - and

then drop thinking? If you did not say, ''I like this, it is mine - it

is my picture, my self-expression, my God, my wife, my virtue - and I am

going to keep it,'' you would have no sense of continuity in time. But

you don't think clearly, right through every problem. There is always

the pleasure which you want to keep and the pain which you want to get

rid of, which means that you think about both, and thought gives

continuity to both. What we call thought is the response of memory, of

association, which is essentially the same as the response of a

computer; and you have to come to the point where you see for yourself

the truth of this.

Most of us do not really want to find out for ourselves what death is;

on the contrary, we want to continue in the known. If my brother, my

son, my wife or husband dies, I am miserable, lonely, self-pitying,

which is what I call sorrow, and I live on in that messy, confused,

miserable state. I divide death from life - the life of quarrels,

bitterness, despair, disappointments, frustrations, humiliations,

insults - because this life I know, and death I don't know. Belief and

dogma satisfy me until I die, and that is what takes place for most of

us.

Now, this sense of continuity which thought gives to consciousness is

quite shallow, as you can see. There is nothing mysterious or ennobling

about it, and when you understand the whole significance of it, you

think - where thought is necessary - clearly, logically, sanely,

unsentimentally, without this constant urge to fulfill, to be or to

become somebody. Then you will know how to live in the present, and

living in the present is dying from moment to moment. You are then able

to inquire because your mind, being unafraid, is without any illusion.

To be without any illusion is absolutely necessary, and illusion exists

only as long as there is fear. When there is no fear, there is no

illusion.

Illusion arises when fear takes root in

security, whether it be in the form of a particular relationship, a

house, a belief, or position and prestige. Fear creates illusion. As

long as fear continues, the mind will be caught in various forms of

illusion, and such a mind cannot possibly understand what death is. We

are now going to inquire into what death is - at least, I will inquire

into it, expose it - but you can understand death, live with it

completely, know the deep, full significance of it, only when there is

no fear and therefore no illusion. To be free of fear is to live

completely in the present, which means that you are not functioning

mechanically in the habit of memory.

Most of us are concerned about reincarnation, or we

want to know whether we continue to live after the body dies, which is

all so trivial. Have we understood the triviality of this desire for

continuity? Do we see that it is merely the process of thinking, the

machine of thought that demands to continue? Once you see that fact, you

realize the utter shallowness, the stupidity of such a demand. Does the

'I' continue after death? Who cares? And what is this 'I' that you want

to continue? Your pleasures and dreams, your hopes, despairs and joys,

your property and the name you bear, your petty little character, and

the knowledge you have acquired in your cramped, narrow life, which has

been added to by professors, by literary people, by artists. That is

what you want to continue, and that is all.

Now, whether you are old or young, you have to finish with all that -

you have to finish with it completely, surgically, as a surgeon operates

with a knife. Then the mind is without illusion and without fear;

therefore, it can observe and understand what death is. Fear exists

because of the desire to hold on to what is known. The known is the past

living in the present and modifying the future. That is our life day

after day, year after year, until we die, and how can such a mind

understand something which has no time, no motive, something totally

unknown?

Do you understand? Death is the unknown, and you have ideas about it.

You avoid looking at death, or you rationalize it, saying it is

inevitable, or you have a belief that gives you comfort, hope. But it is

only a mature mind, a mind that is without fear, without illusion,

without this stupid search for self-expression and continuity - it is

only such a mind that can observe and find out what death is because it

knows how to live in the present.

Please follow this. To live in the present is to be without despair,

because there is no hankering after the past and no hope in the future;

therefore, the mind says, ''Today is enough for me.'' It does not avoid

the past or blind itself to the future, but it has understood the

totality of consciousness, which is not only the individual but also the

collective, and therefore there is no 'me' separate from the many. In

understanding the totality of itself, the mind has understood the

particular as well as the universal; therefore, it has cast aside

ambition, snobbishness, social prestige.

All that is completely gone from a mind that is living

wholly in the present, and therefore dying to everything it has known,

every minute of the day. Then you will find, if you have gone that far,

that death and life are one. You are living totally in the present,

completely attentive, without choice, without effort; the mind is always

empty, and from that emptiness you look, you observe, you understand,

and therefore living is dying. What has continuity can never be

creative. Only that which ends can know what it is to create. When life

is also death, there is love, there is truth, there is creation -

because death is the unknown, as truth and love and creation are.

Do you want to ask any questions and discuss what I have been talking

about this morning?

Question: Is dying an act of will, or is it the

unknown itself?

Jiddu Krishnamurti : Sir, have you ever died to your pleasure - just

died to it without arguing, without reacting, without trying to create

special conditions, without asking how you are to give it up, or why you

should give it up? Have you ever done that? You will have to do that

when you die physically, won't you? One can't argue with death. One

can't say to death, ''Give me a few more days to live.'' There is no

effort of will in dying - one just dies. Or have you ever died to any of

your despairs, your ambitions - just given it up, put it aside, as a

leaf that dies in the autumn, without any battle of will, without

anxiety as to what will happen to you if you do? Have you? I am afraid

you have not.

When you leave this tent, die to something that you

cling to - your habit of smoking, your sexual demand, your urge to be

famous as an artist, as a poet, as this or that. Just give it up, just

brush it aside as you would some stupid thing, without effort, without

choice, without decision. If your dying to it is total - and not just

the giving up of cigarettes or of drinking, which you make into a

tremendous issue - you will know what it means to live in the moment

supremely, effortlessly, with all your being; and then, perhaps, a door

may open into the unknown.

Source: Jiddu Krishnamurti Seventh Talk in Saanen,

1963

^Top

Back to Counseling |

|